At dawn in Batsinda, on the outskirts of Kigali, the city reveals its contradictions. Concrete skeletons of unfinished buildings rise beside clusters of iron-sheet houses built incrementally, often without formal approval. Narrow footpaths double as drainage channels, and construction sites operate quietly, sometimes beyond the reach of inspectors.

The scene captures a central tension in Rwanda’s urban transition: a country pursuing highly planned, technology-driven cities while a majority of its urban residents still live outside formal planning systems.

According to Rwanda’s 2023 Voluntary National Review, drawing on the 2021/22 Joint Sector Review on Urbanization and Rural Settlement, about 63% of the country’s urban population lived in unplanned settlements as of 2022.

This pattern reflects broader structural pressures. In its report Rwanda Secondary Cities Urbanization Review 2024–2025, UN-Habitat notes that rapid urban growth, when not matched with affordable housing and effective land management, almost inevitably leads to informality.

In Rwanda’s context, “unplanned settlements” refer to residential areas developed without approved master plans, formal building permits, or adequate access to basic services such as roads, drainage and sanitation. These areas are neither entirely informal nor fully compliant with urban regulations.

A fast-growing urban future

Urbanization is central to Vision 2050, Rwanda’s long-term development strategy. The plan aims to increase the share of the population living in urban areas from 22.9% in 2022 to 70% by 2050, one of the most ambitious urban transitions on the continent.

Yet growth has consistently outpaced the supply of serviced land and affordable housing.

“Urbanization in Rwanda is advancing faster than the supply of serviced land and affordable housing,” says Semana Pontien, an urban development specialist with UN-Habitat Rwanda. “Without deliberate inclusion, cities risk formalizing inequality rather than reducing it.”

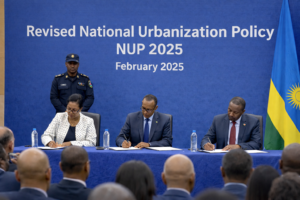

In response, the government adopted a revised National Urbanization Policy (NUP 2025) in February 2025, replacing the 2015 framework whose implementation struggled to contain informal expansion.

While the earlier policy laid strong foundations, its impact was uneven.

“Policy design was strong, but implementation capacity, especially at district level, remained a major bottleneck,” says Engineer Uwimana Faustin, a senior urban planner familiar with the rollout. Budget constraints, weak coordination, and limited enforcement capacity allowed informal settlements to expand, particularly along fast-growing urban corridors.

Speaking at a media training in Rubavu in October 2025, Uwayezu Servile, an economist at the Ministry of Infrastructure (MININFRA), acknowledged these challenges.

“We have planning standards in place, but enforcement has struggled to keep pace with rapid urban growth,” he said. “That gap has created room for irregular construction and informality.”

Digitizing urban control

The revised NUP 2025 marks a shift in approach. Digital tools are now positioned as instruments to improve transparency, reduce discretion, and restore public oversight in urban governance, aligning with Rwanda’s broader investment in Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI).

At the April 2025 launch of the policy and a new digital building permit system, Minister of Infrastructure Dr Jimmy Gasore described the reforms as part of Rwanda’s digital transformation under the National Strategy for Transformation (NST2).

“Planning systems must become faster, more transparent and citizen-centred,” he said.

At the centre of this effort is KUBAKA, a national construction-permit management platform operated by the Rwanda Information Society Authority (RISA). Rolled out under the Rwanda Digital Acceleration Project (RDAP) with World Bank support, KUBAKA is designed to standardize building approvals and limit discretionary decision-making.

In practical terms, the system uses automated rule-checks, commonly referred to as algorithms, to verify whether a proposed building complies with approved zoning, density limits, and environmental standards.

“KUBAKA creates a clear and traceable pathway for every construction permit application,” says Dr Kimonyo Dan, an expert involved in the rollout. “It reduces informal interference and improves predictability for applicants.”

The platform replaces the Building Permit Management Information System (BPMIS) introduced in 2016. Applicants can now submit documents online, track progress in real time, and receive permits digitally.

According to Alphonse Rukaburandekwe, Director General of the Rwanda Housing Authority, the reform aims to ensure that “urban growth follows approved master plans, respects environmental requirements, and adopts required density standards.”

Speed is its most visible promise. Processes that once took weeks are now expected to take days if applications are complete.

When digital systems meet real lives

For some, the platform works.

In Bugesera, small contractor Jean de Dieu Nshimiyimana says KUBAKA helped him regularize a residential project after earlier delays. “Before, I had to move from office to office. Now I can see exactly where my file is,” he says.

But for others, access remains elusive.

In Rwamagana, Marie Mukansanga, a resident expanding her family home, says she abandoned the process altogether. “I don’t own a smartphone, and cyber cafés charge money I don’t always have,” she explains. “I didn’t understand the technical language on the platform.”

The risk of digital exclusion

World Bank project documents 2024-2025 caution that digital efficiency does not automatically translate into inclusion. “Barriers such as the cost of internet bundles, limited access to smartphones, low digital literacy, language barriers, and the absence of local support desks risk excluding low-income households” say the documents.

As of January 2025, Rwanda had 4.93 million internet users, an internet penetration rate of 34.2%, according to DataReportal.

“There are also concerns about data security and oversight as more public services move online,” warns Kamanayo Cyimana Anatole, a Kigali-based digital rights advocate.

Housing-rights groups echo the concern.

“A digital platform cannot replace local guidance,” says Nyirafaranga Nancy Caroline, a housing-rights advocate in Rwamagana. “Without community-level assistance, small builders remain locked out of the formal system.”

On its website, UN-Habitat has repeatedly warned against equating smart cities with technology alone.

“A smart city is not defined by platforms,” the agency notes. “It is defined by how well it serves all residents, especially the most vulnerable.”

Who will measure success?

As implementation of NUP 2025 accelerates, accountability becomes central. Monitoring responsibility lies with MININFRA, district authorities, and the National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR), which tracks urban housing indicators through household surveys and administrative data.

Success will be measured by reductions in new unplanned settlements, faster permit approval times, increased compliance rates, and improved access to affordable housing, according to policy documents.

“Digital reforms work best when citizen feedback is built into the system and acted upon,” says Dr Kamanayo Oscar, a private expert monitoring public-sector digitalization.

A high-stakes wager

From Kigali’s outskirts to secondary cities such as Rwamagana and Bugesera, Rwanda’s urban future is being shaped by rules embedded in software as much as by concrete and asphalt.

“The success of digital urban reform should not be measured by how many platforms are launched,” says Engineer Shirimpumu Sam, “but by whether they expand opportunity, dignity and belonging for ordinary citizens.”

Rwanda has placed a bold wager on technology to bring order to rapid urban growth. Whether it succeeds will depend on whether digital tools help build not just smarter cities, but fairer ones.